From the beginning of the Civil War, the United States government considered Fort Alcatraz to be one of the strongest and most formidable military fortifications in the entire country. As rumors came to light that Southern sympathizers were plotting to separate San Francisco and its wealth from the Union, Fort Alcatraz’s coastal defense position became even more significant. A series of events at Fort Alcatraz illustrated both some admirable aspects of war as well as some chilling ones. During the Civil War, the country’s new division pitted brother against brother, turning former friends and allies into enemies. Fort Alcatraz became a political backdrop, illustrating how war and rumors called certain people’s military allegiance into question.

According to Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, Commander of the Department of the Pacific, U.S. Army, “I have heard foolish talk about an attempt to seize the strongholds of government under my charge. Knowing this, I have prepared for emergencies, and will defend the property of the United States with every resource at my command and with the last drop of blood in my body.”

Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston’s role during the Civil War tells a compelling story about duty and loyalty during wartime. Johnston, born in Kentucky and raised in Texas, served in three different armies: the Texas Army, the United States Army and the Confederate States Army. Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States, considered Johnston to be the finest military officer in the United States. By January 1861, while still a member of the Union Army, Johnston was rewarded with the appointment of Commander of the Department of the Pacific in California; one of his many responsibilities included the protection of Fort Alcatraz.

Despite Johnston’s great military experience and leadership capabilities, his southern roots and association with Jefferson Davis undermined the public’s faith in his commitment to defend the Golden Gate from potential southern attack. Many San Francisco citizens who questioned his loyalty spread rumors that local confederates had approached him to seek his help in attacking the city.

However, while Colonel Johnston served the Union Army, he did faithfully fulfill his duty to calm the threat of war locally and to protect San Francisco. Fearing an attack on Benicia Arsenal, he ordered the transfer of rifles and ammunition to Alcatraz for safekeeping. Johnston also ordered the acceleration of Fort Point’s construction and demanded that they position its first mounted guns to defend against attacks from the city. Colonel Johnston directed those under him to maintain calm among San Francisco’s civilian population and provided additional troops to defend their posts against any attempts to seize them.

While the Union Army was confident that Colonel Johnston would not do anything dishonorable, they feared that he was still too vulnerable to potential Southern influence. In April 1861, Colonel Johnston was relieved of his post. After returning to the South, Johnston accepted a commission as general in the Confederate Army and died at the Battle of Shiloh as one of the greatest heroes of the Confederacy.

The first threat to California’s security occurred in March, 1863. The Union government learned that a group of Confederate sympathizers planned to arm a schooner, the J.M. Chapman, use it to capture a steamship which would raid commerce in the Pacific and threaten to blockade the harbor and lay siege to the forts. However, the Confederates’ plans were thwarted when their ship captain bragged about their scheme in a tavern.

On the night the Chapman was to sail, the U.S. Navy seized the ship, arrested the crew and towed the Chapman to Alcatraz, where an inspection revealed cannons, ammunition, supplies and fifteen hiding men. One of these men, a prominent San Franciscan, had papers signed by Confederate President Jefferson Davis ensuring him an officer’s commission in the Confederate Navy as a reward for this daring plot.

Rather than becoming Confederate heroes, the three ringleaders were arrested as traitors and confined in the Alcatraz guardhouse basement during the investigation. After a quick trial and conviction for treason, they were spared ten years imprisonment on Alcatraz by a pardon from President Lincoln. The Unionists in San Francisco were shocked by the incident and feared that other Confederates were plotting in their midst.

In October 1863, an unidentified warship entered San Francisco Bay. Because there was no wind, the flag hung limp and men in rowboats towed the ship. The ship did not head toward the San Francisco docks but instead, made way towards Angel Island and the army arsenal and navy shipyard. The commanding officer at Alcatraz had a duty to ensure that no hostile warship entered the bay.

Captain William A. Winder, Post Commander, ordered the Alcatraz artillery to fire a blank charge as a signal for the ship to stop. The rowboats continued pulling the ship. Winder then ordered his men to fire an empty shell toward the bow of the ship, a challenge to submit to the local authority. The ship halted and responded with gunfire, which Winder confirmed was a 21-gun salute. Through the smoke, the Alcatraz troops could finally see the British flag waving on the H.M.S. Sutlej, flagship of Admiral John Kingcome. Alcatraz responded with a return salute.

Soon messages were exchanged rather than gunfire. As Commander-in-Chief of the Royal Navy’s Pacific Squadron, Kingcome wrote that he was displeased at his reception in San Francisco. Captain Winder explained his actions by saying, “The ship’s direction was so unusual I deemed it my duty to bring her to and ascertain her character.” The U.S. Commander of the Department of the Pacific supported Winder and replied that Kingcome had ignored the established procedures for entering a foreign port during war. Winder later received a letter of gentle reminder to act cautiously. Many San Franciscans applauded Winder’s actions knowing that Great Britain favored the Confederacy.

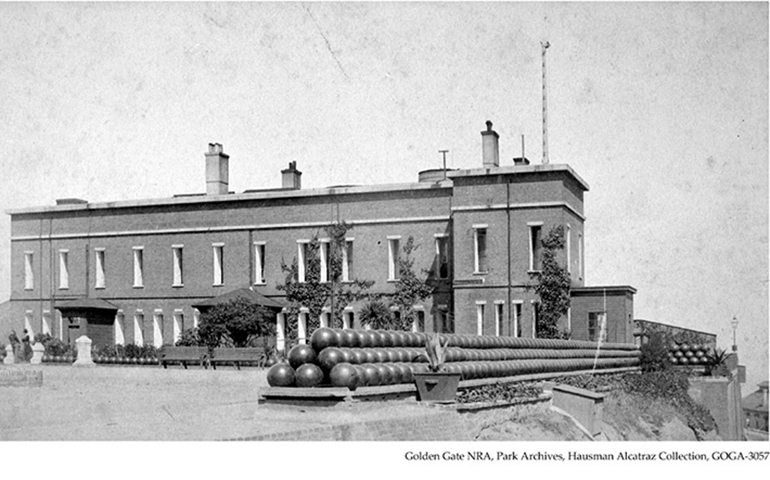

Out of pride for Alcatraz’s grand fortifications, the Fort Alcatraz commander Captain Winder authorized noted commercial photographers Bradley and Rufolson to take photos of the island in the summer of 1864. The photographers were very thorough, capturing fifty different views of the island, including the Citadel, the dock, the soldiers’ barracks and every road and gun battery on the island. In order to offset the photographers’ expenses, prints of the photographs were to be made into portfolios and sold to the public for $200 a set.

However, the War Department in Washington, D.C. did not commend Winder for his initiative and pride in his post, but rather questioned Winder’s motives because his father was an officer in the Confederate Army. The Secretary of War ordered all the prints and negatives to be confiscated as a threat to national security. Later, Captain Winder humbly requested a transfer to Point San Jose, a small defense post on the mainland, later renamed Fort Mason.

Besides dividing the nation, the Civil War sometimes divided families, especially in the border states of Maryland, Missouri and Kentucky where slaveholding was legal but Union sentiment was also strong. The family of Captain William A. Winder was one example, and their commitment to the Confederacy cast the pall of suspicion on the commander of Fort Alcatraz.

One local newspaper stated that while commanding Alcatraz, Captain Winder “was feeding the rebel prisoners held there on the fat of the land and from silver plates.” This printed exaggeration was a particularly charged assertion because his father, Brigadier General John H. Winder, was vilified in the North as the Confederate officer in charge of prisoner of war camps for Union Soldiers, camps notorious because of near-starvation rations and unhealthy conditions.

Two of Captain William Winder’s half-brothers were also captains in staff positions for the Confederate Army, while his second cousin, Brigadier General Charles S. Winder died in combat at the head of the famous Stonewall Brigade, an elite unit once commanded by Stonewall Jackson himself!

Given the number of Confederates in Captain Winder’s family, it was no wonder that criticism mounted in the wake of the Bradley and Rulfolson photography fiasco to the point that the Alcatraz garrison was reinforced by a contingent whose officer-in-charge outranked Winder. Chastened and humbled, Captain Winder sought transfer and the army reassigned him to the command of the Fort Mason post for the remainder of the war. Shortly thereafter, he resigned his commission. Nevertheless, in later years, Winder received testimonials for his loyal service from a number of influential officers, including the Commander of the Department of California, Brigadier General George Wright, who wrote, “I was fully convinced of his loyalty to the Government. At the frequent inspections I made of Alcatraz during his command, I always found everything in the most perfect order and satisfactory condition. His system of alarm signals to prevent surprise and general preparations to meet any emergency, evinced a thorough knowledge of his duty and responsibility of the most important defense of the harbor and city of San Francisco.” (from a report in an 1894 Congressional Edition)

As the Civil War lingered on and the Union seemed likely to win, the U.S. Army was willing to devote more resources to the Pacific Coast. The end of the bloodshed came in sight when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia on April 9, 1865. Unlike the news of the beginning of the war, which took twelve days to reach California on horseback, the news of its end quickly reached San Francisco via telegraph. The city erupted in great celebration, with citizens cheering in the streets and guns booming from many of the forts around the bay. Less than a week later, on April 15th, another telegraph came bringing less joyous news…the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. This time the city descended into chaos. Pro-Union mobs ransacked the offices of a local Confederate newspaper and attacked many citizens thought to be pro-Confederate. The military ordered artillerymen from Fort Alcatraz into the city to maintain order, prevent rioting and punish anyone who was bold enough to rejoice in the tragedy. Confederate sympathizers throughout California who celebrated Lincoln’s death, were arrested and imprisoned on Alcatraz. During the city’s official mourning period, Alcatraz’s batteries were given the honor of sending out a half-hourly cannon shot over the bay as a symbol of the nation’s grief.

惡魔島對內戰的貢獻